Ottawa has plenty of land for new homes

Highlights from the annual Greenfield Residential Land Survey

There’s enough greenfield residential land in Ottawa to support housing growth for the next 25 years. That’s according to the City’s Greenfield Residential Land Survey, presented at this week’s Planning and Housing Committee at City Hall.

(“Greenfield land” includes land parcels within the urban boundary that are designated for future development, including homes and apartments. This land tends to be mostly in the suburbs.)

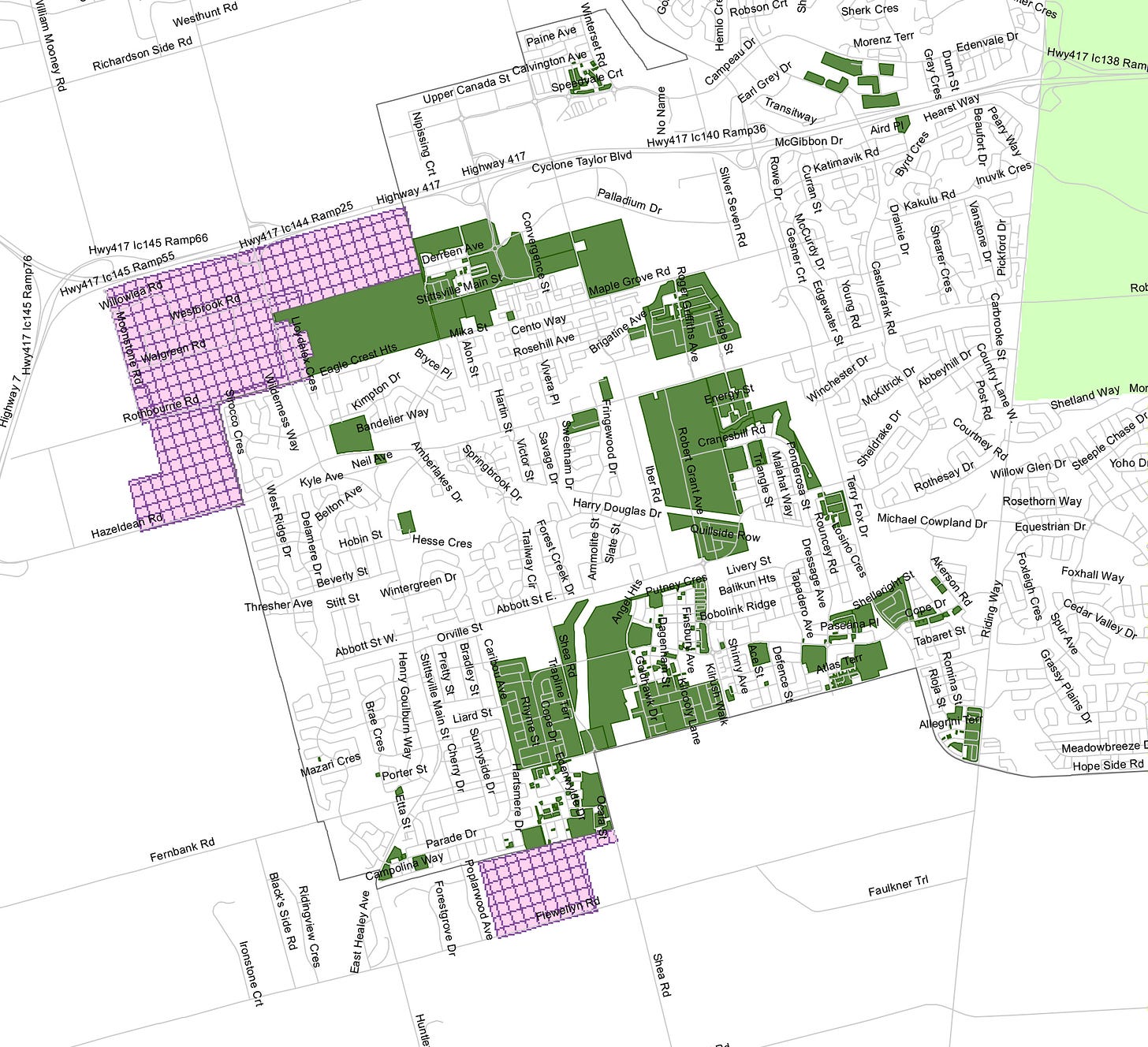

This is always one of my favourite annual reports because it’s full of interesting tidbits about how suburban Ottawa is developing. There’s even a map showing every undeveloped parcel of land, and who owns it. This report covers development up to the middle of 2022.

Within the greenfield land, there are 1,482 hectares that are serviced (or have water and wastewater servicing capacity), with the potential for 64,786 homes.

That’s enough land to last 15.9 years, satisfying Ontario policy requirements for land supply until 2038.

In 2021, City Council approved additional an additional 1,281 hectares of greenfield land that’s expected to support another 23,000 homes, meaning the total projected land supply is about 25 years, taking us to 2047.

From mid-2021 to mid-2022, there were 4,258 housing starts of all types. The most common typology in Ottawa was townhouse (2,399 units) followed by single-detached (1,633).

From mid-2021 to mid-2022, Kanata-Stittsville was the “growthiest” area in Ottawa, where 33% of all the City’s new development occurred.

About 33% of the City’s existing greenfield land supply is in the Kanata-Stittsville area.

Mer Bleue in the east end had the highest development density of 38.0 units per net hectare during the most recent development year. Fernbank in Stittsville was at 33.8 units per net hectare.

You can read the full report and accompanying maps here…

Jeff Leiper, Chair of the Planning & Housing Committee, shared these comments at the end of the meeting:

“This is the fundamental math that determines what the city is going to look like down the road. The province has a policy statement that describes how our city is going to accommodate growth, [and] a requirement that we have an Official Plan that describes how that growth is going to occur.

The math that we've heard today is what describes what that Official Plan is going to say. And then that Official Plan turns into master plans to determine how we're going to build the infrastructure that we need in order to be to accommodate that growth. That turns into development charges that describe how we're going to pay for that growth. And then that turns into a long range financial plan which ultimately winds up becoming a budget discussion year after year.

I think to the public eye it looks like City Council is often dealing with a bunch of one-off decisions… the math that these folks have described is what drives that decision at a very fundamental level and it's important to pay attention to.”

I often get asked by residents: “Why can’t we just stop the growth”. There are a lot of residents who would like City Council to press pause on all (or at least most) new development until infrastructure and services (especially healthcare and schools) catch up.

Leiper’s comments are part of the answer to that question. Ultimately, the Provincial Policy Statement calls for all cities in Ontario to have enough land to support growth for at least 15 years into the future. That’s the foundational policy directive that drives perpetual growth and expansion in our cities, and so much of our planning, budgeting, and decision-making stems from that.

Recommended reading:

Carr: The homeless need help right now — from all levels of government

Here's how much it cost to rent an apartment in Ottawa in December

Lobbying push to expand Ottawa's urban boundary faces local opposition

Ending Homelessness is Possible: Lessons from Finland (video)

Deachman: News flash — LRT did NOT break down in that winter storm